Learning what can not be taught

The illusion of giftedness

If you have ever wanted to be able to acquire a skill, you will have seen this.

Someone who performs it with apparent ease.

It might be photography. One image simply works while others feel cluttered or flat. Or cooking. The quiche has just the right texture, the steak is perfectly timed, the cookies are somehow better than yours despite using the same recipe. In leadership, it may be the person who gets others to collaborate willingly. They convene a room and alignment emerges where others have tried, pushed, explained, and failed.

Being human, we often reach for a comforting explanation: they are just better at this. They were given a gift. We were not.

In the National Library of Australia

Canberra, ACT

When we try and fail to achieve the same results, the conclusion often follows that the skill is simply too hard, or not for us. But this narrative ignores the years of work that mastery usually requires.

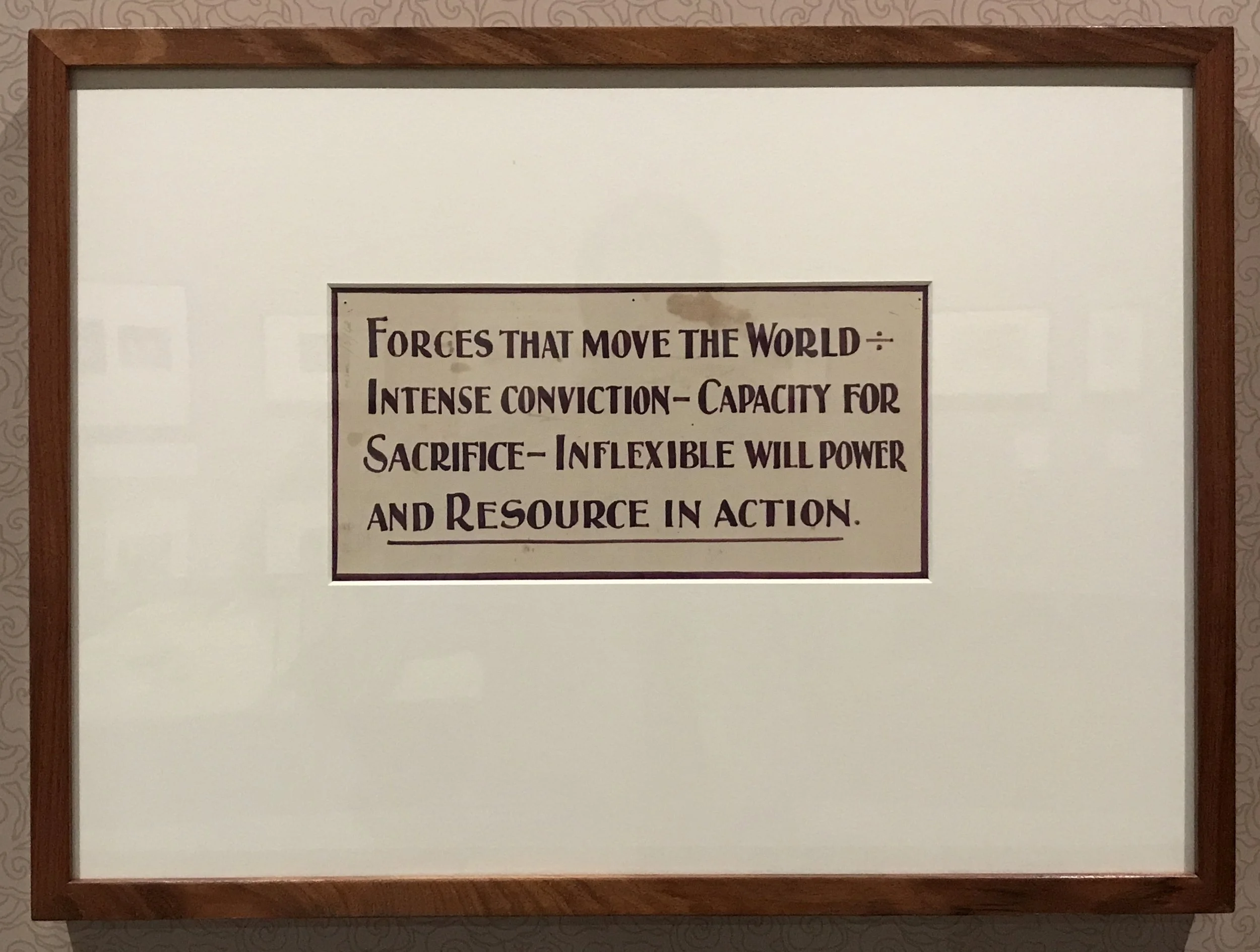

There is a sign, with a quote from former British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, mounted on the wall of the National Library, that reads:

Forges that move the world: Intense conviction. Capacity for sacrifice. Inflexible willpower. And Resource IN Action.

If this rings true, the implication is confronting. To become our best selves (as leaders and as people) requires more than aspiration. It requires sacrifice. It requires being changed by the process of becoming. It demands that we look directly at what gets in the way of our growth: attachment to ease, arrogance, laziness, anxiety, doubt. When indulged, these inner obstacles allow us to cling to the myth of giftedness rather than face the discipline of practice.

Insightful Path book review on this can be found at

(https://www.insightfulpath.com.au/insightful-books/mastery)

And yet, time and again, we know this myth to be false. As George Leonard said in his book, Mastery: the keys to success and long-term fulfillment, most worthwhile achievements arise not from talent, but from persistence and mindful practice over time. Learning rarely follows a smooth, upward curve. Instead, it unfolds through long plateaus where nothing seems to be happening, punctuated by sudden spurts of improvement, only to settle again into another plateau.

This is not ‘failure’. It is the process.

To walk the path of insight requires the humility to see practice itself (including successes and failures) as the teacher. It asks us to relinquish the false idea that being shown a skill is the same as learning that skill.

Because being taught does not guarantee understanding. Understanding does not guarantee knowing. And knowing something does not mean that we now embody it, taking it into who we are.

Where leadership development goes wrong

Most leadership development collapses these distinctions. We assume that exposure equals learning, that explanation equals insight, and that insight equals change.

It doesn’t.

The missing ingredient, again and again, is not intelligence, effort, or even good teaching.

It is humility.

Humility is what allows learning to happen. And humility begins with self-awareness. With the recognition that you are not yet ‘there’. Not as capable as you would like others to think you are, and not yet as capable as the role truly demands.

Laurence J. Peter observed this dynamic in what became known as the Peter Principle: people tend to be promoted based on success in their current role until they reach a level that requires fundamentally different skills. At that point, natural competence runs out. The environment becomes more volatile, more political, more ambiguous. Strategy, judgement, and relational skill matter more than technical expertise.

Some leaders adapt and learn. Others do not.

Those who cannot learn tend to stall. What prevents learning at this level is rarely lack of intelligence. It is an unfamiliarity with the skills of ‘not knowing’. Leaders are so often rewarded for their ability to know things… for their being decisive, right, and for avoiding mistakes while defending their position persuasively.

What many learn through this process is what Harvard Business School, and Yale School of Management professor, Chris Argyris calls, ‘Model 1 behaviour’. That is: controlling the situation, winning arguments, avoiding vulnerability, suppressing negative feelings, and protecting themselves and their organisation from discomfort. These strategies are rewarded early in a career. Over time, they harden into defences that block feedback and shut down learning.

A simple diagnostic is to notice how you receive difficult feedback. Do you try to subtly control the conversation? Rationalise your behaviours? Deflect responsibility? These reactions are usually unconscious and once adaptive… but they are poorly suited to learning.

Wanting to be Taught vs intending to Learn

When I first went to university, and dropped out, and enrolled elsewhere, and dropped out again, it was not because of laziness or lack of ability. I was not brilliant, but I was not a poor student either.

What I was, without realising it, was someone expecting to be taught.

I was looking for the perfect instructor. The right institution. The one place where all the meaning in life and learning about how to thrive and make a difference in this world would finally be delivered to me, intact and complete… and delivered by compassionate and skilled teachers who ‘understood me’.

What life patiently taught me instead was uncomfortable… and liberating:

Your intention in capability development should not be to be taught.

Your intention should be to learn, and perhaps more importantly, to be willing to be changed.

Without seeing it at the time, I now recognise that I was longing for something like the world Science Fiction writer Isaac Asimov imagined in his short story Profession, where knowledge is implanted instantly, efficiently, and without effort. What is lost in that world is precisely what matters most in relation to leadership capability development. That being: judgement, creativity, and the wisdom born of struggle.

Learning is not ‘a transfer’.

It is a relationship.

And relationships require humility.

As Zig Ziglar put it:

If you are not willing to learn, no one can help you. If you are determined to learn, no one can stop you.

Humility on the Mat

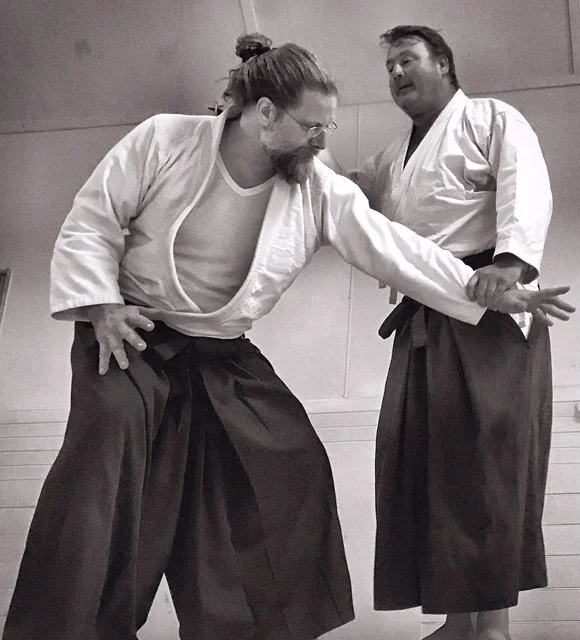

‘before being thrown’

Matthew Sensei and James Samana

Honesty facing one’s inadequacies is uncomfortable. It is easy to avoid this kind of introspection. One practice that reliably brings me back to it, is Aikido.

No matter how long I train, there is always more to learn. Always another realisation about intention, about energy, balance, or even just an angle or balance or skill that I’ve missed. Another habit I didn’t notice. Another way my body reveals an assumption I was carrying.

The training requires both giving and receiving technique. To throw, and be thrown.

Repeatedly.

Not to dominate, but to reveal… and to learn to give and receive the insights of being.

Progress on the mat is not earned by being clever. It is earned by showing up willing to be wrong, willing to fall, willing to practice the basics again… and again…

Humility is not optional here.

Without it, learning simply stops.

The discipline of care fosters humility

In many contemplative traditions, where people are learning to become more aware and to gain insight into their inner hurdles, there is a strong emphasis on tending shared spaces: washing dishes, sweeping floors, making tea for others, and in general, caring for common areas.

These practices are not symbolic add-ons; they are deliberate training.

They make status visible; and then gently neutralise it. The task does not respond to seniority. The work still needs to be done. In this way, care becomes a teacher. It brings people back into relationship with one another and with the whole, reminding us that leadership is not a position above the work, but a responsibility within it.

This matters deeply for the kind of leadership our moment demands.

The problems facing our world today (climate, public trust, inequality, complex system failure) cannot be solved by a single individual, organisation, or nation. They require collaboration across boundaries, disciplines, and perspectives.

That collaboration depends far less on technical brilliance than on relational capacity: the ability to listen, to stay curious, to make space for others, and to work productively with difference.

Yet one of the greatest risks for senior leaders is the quiet pull of status. Leaders rarely stumble because they lack policy knowledge or professional experience. More often, they fall because ego hardens, pride narrows perception, and learning slows.

If public sector craft is about stewarding collective capability in service of the public good, then humility is not a “nice to have.” It is the condition that makes genuine collaboration (and therefore effective leadership) possible.

‘The journey of a thousand miles’

AikiLife Dojo, Phillip, ACT

The Deeper Truth

If we are serious about developing leaders, we must be serious about how learning actually happens.

Humility cannot be taught as a concept. It must be encountered, practised, and earned.

This is why leadership training that remains comfortable will always fall short. Frameworks and models matter, but without experiences that unsettle certainty and soften ego, they do not translate into wiser action. And they definitely do not transfer into a more embodied identity.

Humility is not an optional virtue.

It is the gateway to learning.

If we want leaders who can think, adapt, and act wisely in complexity, then we must design leadership development that gives them opportunities not just to be taught, but to learn.

And most importantly, to let go of their old self in favour for their best self.