The real risk in capability work

Mistaking reach for impact

A practitioner’s note on scale, depth, and why transformation doesn’t obey organisational deadlines.

‘Growth happens at the pace of trust’

National Arboretum, Sunrise

Canberra, ACT

In capability work, there is a familiar seduction: the belief that if we can reach more people, we must therefore be creating more impact. This assumption is so baked into our organisational systems that it often goes unchallenged… even though, empirically, it is not supported by what we know about human learning, behavioural change, or relational capability.

A few years ago, I facilitated a two-day leadership program for a large branch. Day one was on psychological safety; day two was about integrating the concepts into everyday cultural practices. The group was engaged, thoughtful, energised. A few weeks later, one of the executive officers reached out for coaching, and over the next twelve months we worked together to explore and develop skills which resulted in her building new ‘micro-skills’, and achieving her organisational and personal goals.

But back with the group, well…, my coaching counterpart told me that after the first ‘flush of excitement’, the momentum stalled. And after a couple of months, regardless of the training having reached many (some of whom said it was exactly what they needed), it simply wasn’t enough to transform the system.

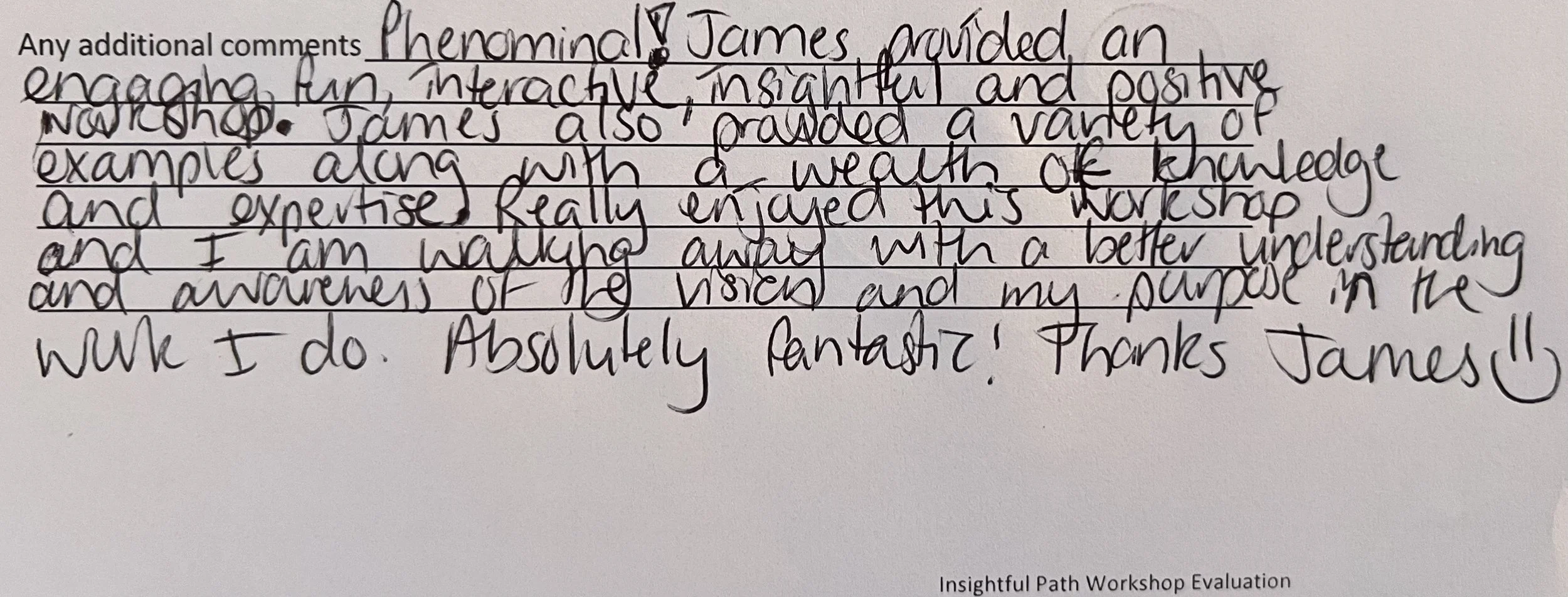

‘Participant feedback on the power of an event for an individual’

Insightful Path Workshop Evaluation

This pattern reveals a deeper tension:

“Systems level transformation must be accompanied by individual level transformation... And this requires trust, courage, and, a familiarity with, and willingness to walk the path of discomfort to explore both character and competence.”

What the research already knows (but we often forget)

Educational theorists like David Kolb have long argued that learning requires a full cycle:

experience → reflection → conceptualisation → experimentation.¹

In practice, this means capability grows through repeated contact, guided practice, and opportunities to try, fail, and recalibrate.

Similarly, Donald Schön’s work on reflection-in-action suggests that professional judgement (especially in complex, relational work) develops only when people are supported to examine their assumptions in real time, within real dilemmas.²

This is not “content transfer”,

This is not “data acquisition”.

This is identity-level, practice-based development.

And identity does not move on a linear schedule.

‘What we see vs what holds the system up’

Alta Azul, Eucalyptus globules, Huon Valley Grove of Giants, Tasmania

Depth outpaces scale

If we take these insights seriously, the implications are uncomfortable for traditional capability models.

A one-off workshop can signal a cultural shift, but it rarely creates one.

High attendance numbers might produce a reassuring graph, but they tell us very little about behaviour change.

Relational capability (listening, inquiry, perspective-taking, judgment under uncertainty) evolves through repeated relational contact, not periodic mass exposure.

There’s also the matter of trust. Trust grows slowly, and anything that grows slowly will always be at odds with performance systems optimised for speed.

As I often tell clients,

“You learn what you earn.”

Insight does not arrive via download.

It arrives through participation, discomfort, reflection, and practice.

‘Conversations at dusk’

Design for the outcome, not the optics

Think about those times when you've had deep realisations. Sometimes they are times when you've had to retreat and take stock of your life. Sometimes it was because of a deeply experienced time with a friend, mentor, or partner. But in these times, we often find ourselves between reflection and thinking and feeling and talking. We drift into and out of conversations, sometimes circling an idea, sometimes sitting in silence. No pressure, no preformance! Just presence. When done together, you can almost see trust forming in real time, shaped by nothing more than shared space and a curiosity to see what can happen in this connection.

Most adult learning environments are the opposite. We compress insight into tight schedules, push reflection into five-minute breaks, and expect trust to appear on cue. Depth comes from the conditions, not the content. It is important to understand this, and that people need room to arrive as themselves before they can start to look at what parts of their current identity they can change. This is why transformational change requires self-awareness, and experiential means have been proven to be effective. As Carl Rogers once said, ‘… the curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.”

If the true aim is impact, then learning design has to prioritise the conditions under which insight happens. That almost always includes:

Experiential methods (experiencing concepts, emotions, identities that enable transformation)

Guided reflection (structured questions, facilitated debriefs after incident debriefs, case in point)

Real dilemmas (not hypotheticals chosen for convenience)

Smaller groups where trust can form

Longitudinal contact rather than isolated touchpoints

This is not indulgence;

it is evidence-based.

Experiential and practice-led methods consistently outperform passive content delivery in developing relational and leadership capability.³

‘Form follows function’

From the Artists’ Woodshed (and stone shed!) Retreat

And importantly: form must follow function.

If the function is deep, transformational change, then it is incredibly difficult to achieve in a single session for a hundred people.

The deeper question for leaders

The real question is not:

“How many people did we reach?”

It is:

“What kind of learning do we want to enable, and what is required for that learning to matter?”

Real impact is not mass attendance.

Real impact is the moment someone slows down enough to see their assumptions.

Or the moment they catch themselves choosing curiosity over defensiveness.

Or the moment two colleagues repair trust after months of quiet avoidance.

These shifts are subtle, slow, and deeply relational.

They cannot be rushed.

They cannot be scaled prematurely.

They can only be earned.

References

David Kolb, Experiential Learning, 1984.

Donald Schön, The Reflective Practitioner, 1983.

Beard & Wilson, Experiential Learning: A Handbook for Education, Training and Coaching, 2013.