The Screwtape Letters

The whisper in the boardroom:

What C.S.Lewis teaches us about modern leadership

‘Letters from the ‘lower-archy’: written for us all’

From the Insightful Path Library

I have many ‘friends on the shelf’ - and C.S. Lewis is one of them.

Lewis wrote the Screwtape Letters in 1941, as the Second World War raged across Europe. The book was written to show that what is important in relation to leadership was not about what happens in the headlines, but about the habits of the human heart.

And that is what makes it so enduringly relevant to leaders today, who may imagine that ‘success’ or ‘failure’ arrives all at once in a dramatic moment, a decision, a fall, a breakthrough.

Lewis knew better. His book leads one to see that neither ‘ruin’, nor ‘redemption’ are sudden. They are built, step by step, out of small choices and rationalisations, the subtle self-deceptions, the ‘little things’ that add up… the daily ways of being that quietly shape who we become. Our failures are really the accumulation of unexamined habits… and for success it is the long, invisible cultivation of attention and integrity.

Lewis’s ‘The Screwtape Letters’ can be read as his insights on the importance of cultivating integrity, and of how to identify and face any number of challenges… essentially, how we can bring our best self into the world.

This is why I include C.S. Lewis’ book, The Screwtape Letters in the Insightful Path Library. Because his lessons are equally relevant in today’s context.

The Chronicles of Narnia

From the Insightful Path Library

I first met Lewis, like many of my generation, through reading The Chronicles of Narnia as a child. But it was later, through his fiction, science fiction, essays, and writing across genres, especially, The Screwtape letters, where I realised the depth of his insight.

Dedicated to his friend, J.R.R. Tolkien, this short, satirical novel unfolds through letters from a senior devil Screwtape, to his nephew, Wormwood, a ‘junior tempter’.

The irony is that Lewis wasn’t warning us about them, he was warning us about… us.

Lewis understood something that psychology and leadership science would only later articulate: That our greatest moral dangers are not the dramatic ones. They are the subtle, reasonable ones.

‘The safest road to Hell,’ Screwtape writes, ‘is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot.’

1963 Book: by Hannah Arendt on convicted Nazi, Adolf Eichmann,

Lewis’s insight anticipates what political theorist Hannah Arendt would later observe in Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the banality of evil. This was her controversial report on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust. Expecting to find a monster, Arendt instead found an ordinary man who insisted he was ‘just following orders'‘. From this, she coined the phrase ‘the banality of evil’, suggesting that great atrocities are often carried out not by fanatics or sociopaths, but by dutiful, compliant individuals who stop thinking for themselves.

Arendt wrote that Eichmann had ‘…ceased to live according to… principles… and consoled himself with the thoughts that he no longer was master of his own deeds,…. that he was unable to change anything.’

That Eichmann justified his lack of courage as an ‘act of realism’. This is the language of resignation, of one who senses things are wrong, but convince themselves that nothing can be done. Eichmann’s excuse was obedience.

From the Insightful Path Library

And yet there have always been voices urging us to resist surrendering to 'obedience’. One of them came two centuries earlier, from the American revolutionary pamphleteer, Thomas Paine, who, in an age of upheaval reminded his readers that,

‘We have it within our power to begin the world over again’.

The courage to begin again.

To rebuild conscience, clarity, and compassion.

This has always been the antidote to corruption, whether personal or institutional. But Pain also issued a warning that echoes eerily in our own time:

“I am inclined to believe that all those who espouse reconciliation [with the King] may be included within the following descriptions: interested men, who are not to be trusted; weak men, who cannot see; prejudiced men who will not see; and a certain set of moderate men who think better of the world than it deserves — and this last class, by their ill-judged deliberations, will be the cause of more calamities than all the other three.”

Paine saw what Lewis later described in The Screwtape Letters: That evil often thrives not in cruelty, but in corrupt slides into compromise. It hides in those who mistake comfort for wisdom and who choose to not see what conscience demands they confront.

In both men’s eyes, the danger was not passion, but passivity. Not the loud wrong, but the quiet avoidance of what is right.

‘Insights from your ‘best self’’

Credit: Unsplash.com

Photographer: Benjamin Child

What is required for leadership at times like that, is the practice of bringing what is unacknowledged into awareness for us as leaders. That we will need to reconnect with our best selves if we are going to be able to ‘recreate our world’.

Lewis understood something that psychology and leadership science would later confirm: our greatest moral dangers are not the dramatic ones, but the ‘subtle, reasonable ones.’

“The safest road to Hell is the gradual one- the gentle slop, soft underfoot.”

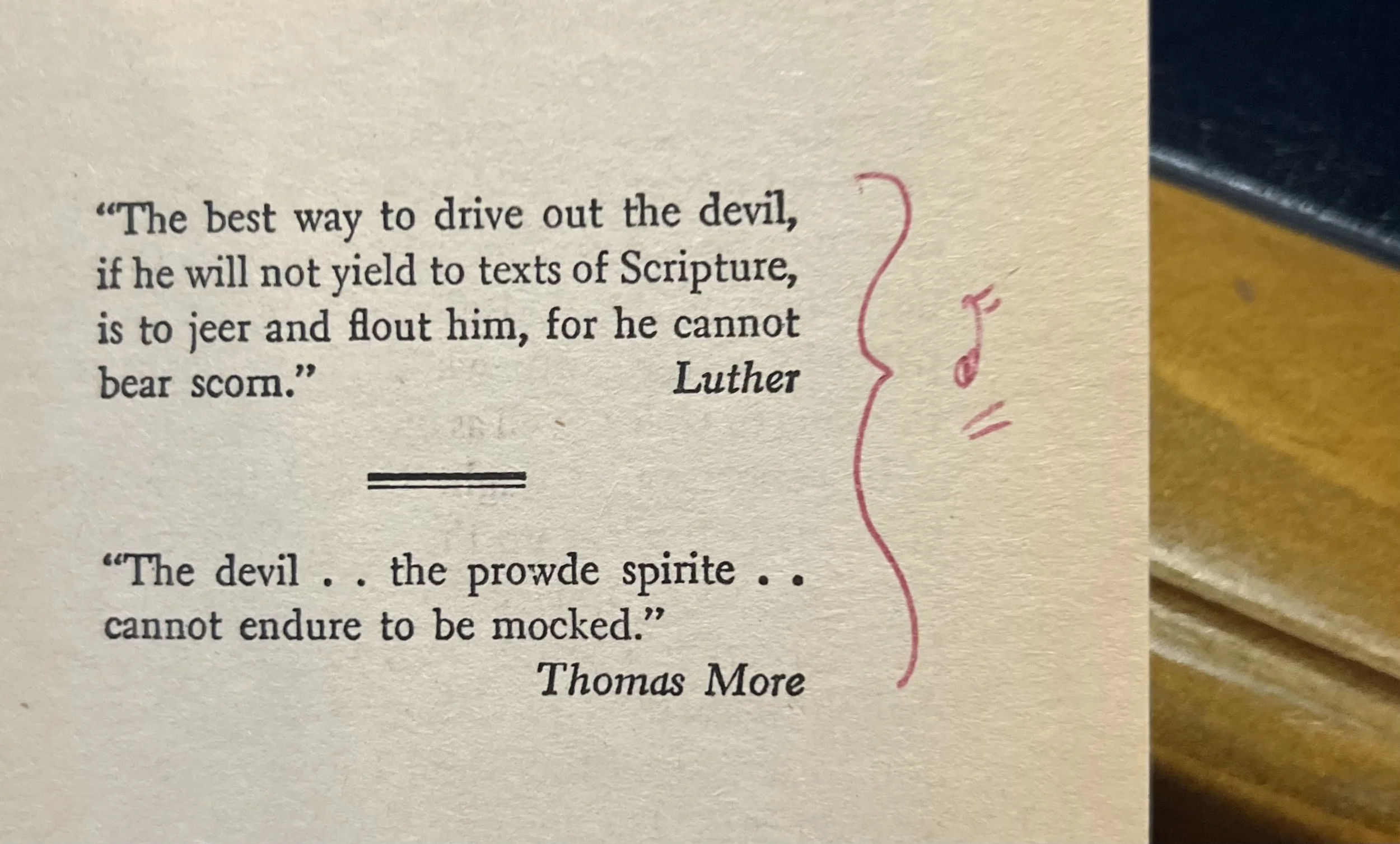

‘Temptation, footnoted’

From the Insightful Path Library

Leadership failures, in Lewis’s vision, are only revealed in the big spotlight, they are created in the habits of thought, the rationalisations we tell ourselves. That we ‘are doing fine’, That the compromise on this thing, or that, are only temporary. That empathy is dangerous and efficiency is more important.

But a critical component of leadership begins in awareness. Awareness of even the risks to values-driven leadership such as unexamined comforts, such as free speech, and our reactions to criticism.

‘Ego spotting’

Page 5

If you want to strengthen your ability to ‘hear the inner voices’ of insight that Lewis believed accompany us on our paths, ask yourself these questions:

Where am I tempted to justify something small that compromises something large?

What inner voice keeps me ‘safe’… but small?

Where might I begin the world over again… starting with myself?

Lewis use his letters as metaphors for attention, integrity, and the ongoing battle to stay awake.

He reminds us of our need to build the courage required to lead on your own path to insight.

If this reflection stirs something… a question about your own leadership, or about how subtle habits shape the culture around you… that’s the quiet beginning of what could be a productive coaching conversation, and could help you to hear your inner whisper, before it becomes your identity, your story.

And, perhaps, this string could help you to find the courage to begin the world over again… one decision, one conversation, one act of awareness at a time.