Wrestling with Daedalus

Preamble: ‘What I Wrestled With’

This post isn’t just about carving. Or sculpture.

It’s about the quiet questions that rose while I shaped a fallen tree trunk in my shed—and how they spoke to me as an artist, a son, and a father.

It’s about legacy, love, and letting go. About the myths we inherit and the ones we pass on. And about how we make something meaningful—knowing we can’t control how it will be received, understood, or remembered.

In this reflection, I ask:

How do we offer something enduring? A work of art, a lesson, a value… all the while, knowing it will be taken into hands and lives beyond our control?

How do we listen to the materials around us? Discarded wood, inherited stories, old wounds… and help them to find voice in their new forms?

How do we honour the people and places we come from, without being confined, or defined, by them?

And how do we create something that lives not just in the private realm, but in the world… even when we know it may be misunderstood, yet vowing to allow this to matter?

In wrestling with Daedalus, I am reminded again that the act of making is not only about form or function… but about entering the space between control and release, between love and letting go.

“Hope and Anguish”

The Artists’ Woodshed Retreat

When the carving speaks

This weekend, I found myself wrestling with Daedalus.

Not the man himself, of course—but a rough trunk of wood I’d cut down in the yard. It was destined for the firewood pile, until something about it made me stop. The shape, the grain, the quiet weight of it in my hands.

As I turned it over, I began to see things—wings, a torso, arms outstretched. A face tilted to the sky, caught somewhere between hope and anguish. And behind that face, I saw a father.

“Finding Daedalus”

The Artists’ Woodshed Retreat

It wasn’t an ordinary weekend. I’d been invited to a family reunion—half a world away, in a country that’s drifting toward ideals I can’t stand behind. I wanted to be there. I miss them. My kind. My blood. But instead, I found myself alone, not with family of origin, but with something older—myth, memory, and wood.

And in that, I found Daedalus.

I saw him in the timber. I saw him in my own father, now gone. And I saw him in myself—somewhere between the roles of son and father, still working out what each one means.

That space—between the old way and the new, between what’s passed down and what must be re-formed—that’s where myth begins to speak. Joseph Campbell wrote that myth has four functions: to stir awe, explain the world, support social order, and help us grow through life’s stages.

It’s that last one that lands hardest for me.

Because when I’m carving—whether it’s from wood or from memory—I’m shaping something I can’t quite say. It’s not therapy. It’s not performance. It’s just a way to take the tangle inside and work it into form.

Myth, memory, family stories—these are tools. They help us hold the weight of what we didn’t choose but still carry. And when we do that honestly—with whatever materials we have—it can make us more grounded. As fathers. As makers. As people who want to live with integrity.

Still—some days, adulting is hard.

Especially when the legacy you’ve inherited feels both noble and heavy in your hands.

“The carving of a myth”

The Artists’ Woodshed Retreat

The carving of a myth

One of the lessons of dealing with stress, is to get into a space where you can respond, rather than react. Connecting with what arises from the creation of art, is one of the ways I learn to be more responsive. And so, I went ‘to the shed’. I needed to sort things out, in my minds, through my hands. Through my Soul.

There, I pulled out the tree trunk, cut from my own yard. It held the memory of place; its weight and grain shaped by weather and time. It had been destined for firewood, but something about its form asked to be seen, not burned. This wasn’t just material, it was a conversation with site, and a rescue of presence. I began to carve… first rough and earnest lines of shape, which were then made smooth and more refined… more searching. And slowly, a figure emerged. A body straining mid-flight. Wings extended. Not symmetrical. Not perfect. But speaking.

The face tilted upward… hopeful, anguished, transcendent. And in it, I saw the beginnings of Daedalus.

“Wrestling with Deadalus”

The Artists’ Woodshed Retreat

Not just the father of Icarus, but Daedalus the maker. The architect. The sculptor. The man whose creations were said to pulse with life. According to myth, as a sculptor, his statues were so real that Heracles, mistaking one for a living threat, struck it down with his club… only to discover it was a sculpture of the demigod himself.

Daedalus was the sculptor, the novel creator, who first added pupils to the eyes of statues. Who carved not just form, but motion. Who gave stone the illusion of breath.

This was the man I saw in the wood. A figure of genius and contradiction… visionary and exile, creator and destroyer, artist and father.

And so the face in the carving (rough and unfinished as it still is) echoed not just a myth, but a man wrestling with the limits of his own creation.

The weight of knowing

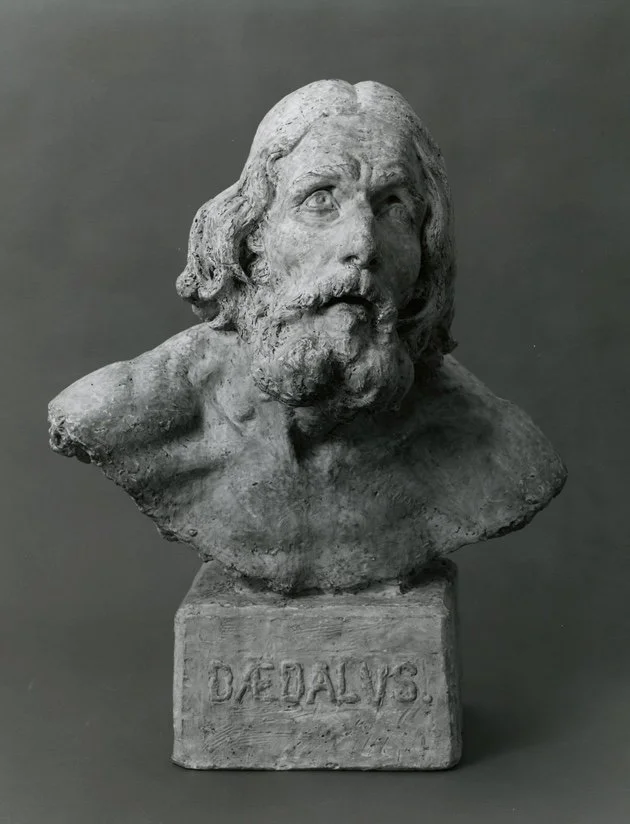

‘Daedalus’

Charles Grafly

28×20×14 in

Painted Plaster

His eyes, like those in Charles Grafly’s sculpture of Daedalus (above), held that tension: the desperate hope that his boy might still find a way to survive, to pull it off, despite everything. And at the same time, the quiet anguish of a father who already knows the fate that’s unfolding. Who has warned, who has gifted, and who now can only watch.

“Learning to fly”

The Artist’s Woodshed Retreat

And the moment I wanted to capture, the moment I think Grafly captured, was the moment that Daedalus realises the disaster that will strike his offspring, in which his eyes transition from hope to anguish. It is the moment of causing pain, in which we first see the flicker of grief.

For Daedalus this was the moment he saw Icarus start to loose control… the moment when Icarus himself, is yet to realise, but has shifted in his winged sling, high above the earth. It is the moment in which Daedalus’ eyes shift from his hopeful to more full of pain and grief.

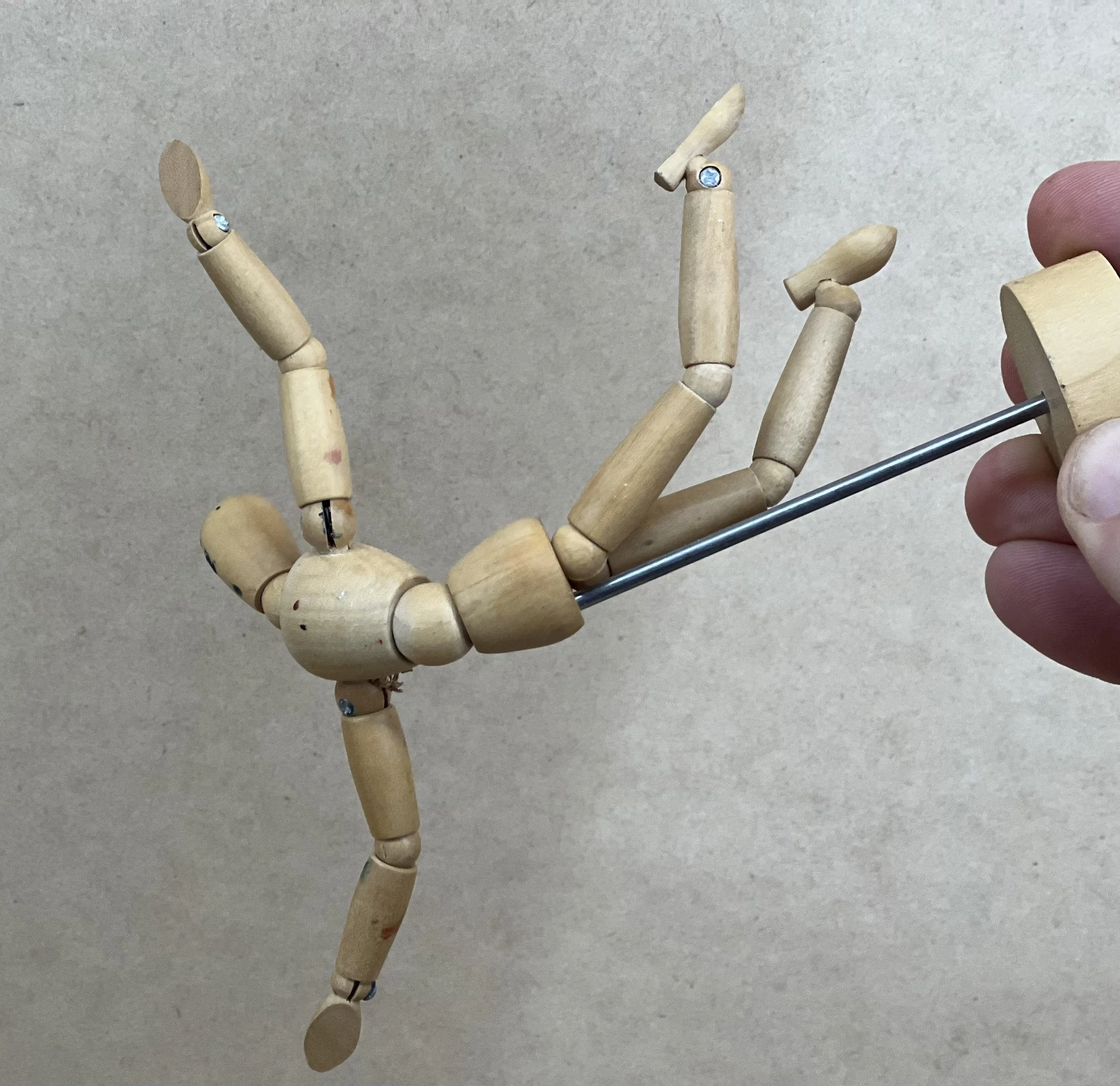

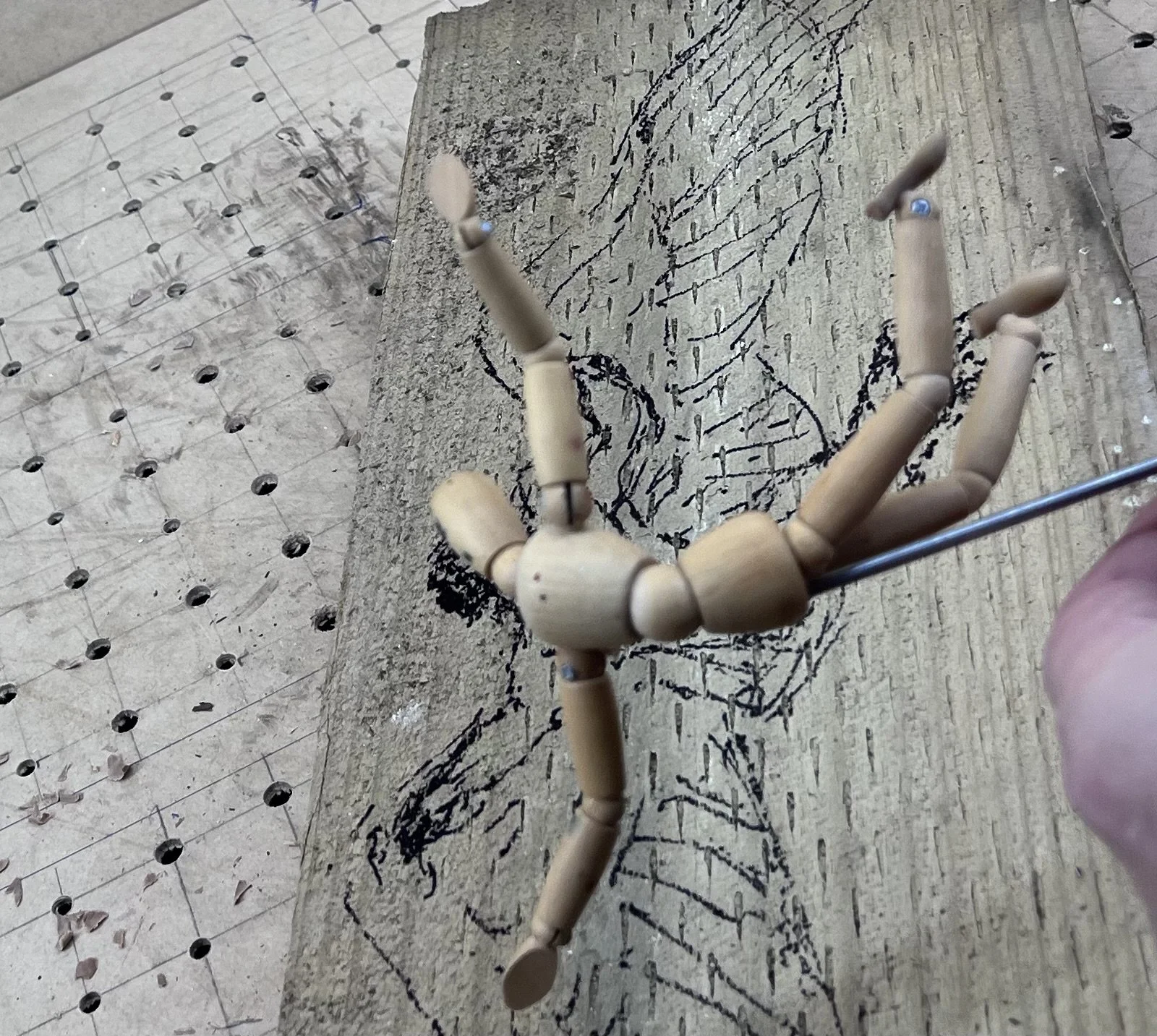

To help me capture this moment for Icarus, I turned to another heirloom - filled with experience and power. This time, my grandmother’s old artist’s mannequin, a tool she had used in her own drawings.

With it, I tried to find Icarus: his posture, his shape, his moment. That last beat of control before chaos. Before descent.And in shaping him, I began to shape myself.

‘living deeply’

Nebraska, USA, just off the Oregon Trail

I was once ‘Icarus’… the boy who read ‘Life in the woods’ (Walden) by Henry David Thoreau, and likewise yearned to ‘live deep, and suck out all the marrow of life’. The boy who tested boundaries. Who sought meaning, insight, even if it brought pain. Who wanted to change the world, and sometimes still does.

And my Dad… well, he saw the world, … Or at least he would say, he saw the world…. ‘clearly’.

Dad urged caution. He believed you could only hope to change those near you. And yet, and this is important, he also deeply admired the ones who did more: MLK, who shifted the course of justice for so many. Helen Keller, who emerged from silence into a life of profound impact. And he admired those who became heroes of mine, like Anne Sullivan, who reached into that darkness with persistence and love to help Keller find a way into her own best self.

But in his admiration of those heroes, my Dad carried a contradiction. He warned me not to fly too high, and yet quietly wished I might. Dad hoped, beyond hope, that I might be one of the rare ones. The ones who were able to live a life, where they knew their work mattered, and helped to advance the plight of us all. That perhaps, I could ‘put on the wings and still survive’.

And it is, as of yet, too early to tell… but I remain, ever hopeful.

‘Ever Hopeful: The first dream of Icarus’

The Artist’s Woodshed Retreat

So, in carving Icarus, I’m carving more than just the boy. It’s the moment before his fall. The exact breath before the boy Icarus realises what’s coming, and will not be able to stop it, and the moment the man, Daedalus has already seen it. His body is still aloft, but the failure has already begun.

That is the moment in Icarus’s story that will help me find my Daedalus. I need to 'see’ what Daedalus sees in Icarus, in that one moment. And in shaping that moment, I began to feel what Daedalus must have seen from below. That terrible flash when the father realises, even before the son, that fate has stepped in.

And so, I returned to Daedalus, not just to carve him, but to understand him. Which brings me to another version of the Daedalus story.

In it, Daedalus and Icarus escape by boat, improvising sails from sheets and cloth. They don’t fly; they sail.

And even then, the sea claims the boy.

It’s not hubris that causes the fall this time. It’s fate. It was the injustice of the fates, and the ill-will that occurs in the interplay between ‘man’ and ‘justice’, and the ‘legacy’ that could be. This story led me down the next path as I wrestled with Daedalus.

“The Laocoon’s Scream”

Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus

On that path, I remembered the father who wrestled with the injustice of the Gods. Laocoon, a character in Virgil’s Aeneid, and a man who saw what others didn’t. Who warned his people about those ‘bearing gifts’. A man who pleaded, who knew…and still, could not stop what came next. The gods sent sea serpents to silence him and his sons.

His face, captured forever in marble by Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus, is a masterclass in anguish. But it’s not just fear. It’s the pain of knowing. Of understanding what’s coming, and being powerless to stop it.

“Earnest striving”

The Artist’s Woodshed Retreat

In finding these stories, as they arose from my work, I came to see my own father’s warnings and how they mayn’t have been designed to ‘clip my wings’, but to shield me from wounds he never healed. And perhaps my carving, this wrestling, is part of reimagining that old tension. Not to reject it, but to give it a new form. To reshape the silence between us into something seen… into something I can now SEE, and work with.

“The yearning for flight”

The Artist’s Woodshed Retreat

“The hope of a Father”

The Artist’s Woodshed Retreat

Perhaps that was some of what I wrestled with this weekend. I tried, in my carving, to capture the brashness of youth, and the anguish of loss, yet also the power of myth and healing nature of connection.

I saw this within thought of my own father, now gone. Within the wisdom I once resisted, and through the fact that am only now beginning to understand.

Dad told me: You can’t change the world—only those around you.

And yet, in the same breath, he spoke of those who did change the world.

That contradiction—the realism, and the hope—that’s what I carry now. And what I hope, in some way, to pass to my own children.

“Looking upon one’s legacy”

The Artists’ Woodshed Retreat

Carving toward legacy

Burt as for my legacy? For the gifts I am consciously giving my children, the gifts, I hope, of curiosity, presence, resilience, love… I don’t know if they will be enough. And I don’t know what heights they’ll aim for, or what seas they’ll cross. But I know it’s their flight. Their story. And hopefully I’ve given them the skills to deal with whatever they encounter on their path.

“Flying the path - Insightful”

The Artist’s Woodshed Retreat

And I hope a part of my legacy will be that I was like Daedalus (not perfect, not omniscient) but loving.

And present.

And willing to offer the wings, even when I know what they risk.

G.K. Chesterton once wrote that “anything worth doing is worth doing badly.”

This does not mean, that it’s fine to cut corners, nor to ‘not care’ about things. Rather, it’s a call to begin, even when perfection isn’t possible. But to begin, and strive for that which is worth doing.

And because Chesterton also said: “A life without values worth dying for, is not a life worth living for.”… Perhaps, it is important to do that which is worth doing, even more so, when perfection is beyond reach, yet the values that you are standing for, are living for, are indeed, worth a life of uncovering them in the material you carve your life from.

And so, this weekend, I welcomed insight into the Artists’ Woodshed Retreat, while I carved.

And in the grain of that wood, I remembered the stories that helped me to build values worth living for.

And I tried, in the shape of a mythic figure falling from the sky, to honour a legacy not just of caution, but of courage.

A legacy I now hold… and must learn how to pass on. Skilfully… to those that walk, the insightfulPath.

A Final Reflection

Though carved in solitude, these figures are not meant to stay hidden. Art (like leadership) lives in the world. We shape quietly, but the results are visible. They’re read, responded to, sometimes misunderstood, sometimes embraced.

The same goes for how we show up in teams, in families, in the work we do.

If you’re in a season of change, stepping into something new, carrying something old, and you're looking to clarify your leadership identity, I can help.

I work with leaders, creatives, and change-makers to uncover the values that matter, the voice that resonates, and the path that feels true.

If you're ready to do that work (with focus, presence, and a bit of grit) I’d be honoured to walk alongside you.

Reach out. Let's carve something meaningful, together.